|

| Loraine Hansberry, author of A Raisin in the Sun |

“Where lectures and slide shows do not work, drama does” (Pitman 171). Theater has been a powerful form of art and literature in the western world for centuries. Greeks turned to it for religious expression; Shakespeare turned to it for political expression and comedy. For many years, dramatic production in America was reserved for white men. In the late 1950s, Lorraine Hansberry, an African-American woman who grew up on the south side of Chicago, wrote a play called A Raisin in the Sun, which forever changed the landscape of American theater. Raisin portrays the difficulties associated with deferred dreams and racial issues. Hansberry’s choice of medium translates and expresses the main themes of the play to the audience more powerfully than would a classical literary text for three main reasons: first, the actors and audience participate in the experience together; second, theater induces emotion in the actors and the audience; and third, theater attempts to influence all to look inward, which facilitates change in the individual.

Theater is a unique medium that allows both the actors and the audience to participate simultaneously in a shared experience. Belarie Zatzman, a professor of drama and education at York University in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, focuses much of her work on the concept of shared experience. In an article entitled “The Monologue Project: Drama as a Form of Witnessing,” Zatzman states that the nature of what she calls the “memory-work” that is created through drama is “designed to locate our own narrative and memory—personal, political, and historical,” that relate to the themes of the work (Zatzman 35). As the actors and the audience locate these memories, they are able to fill in the spaces left by the narrative with their own experience. This interaction creates a new landscape, where remembered, forgotten, unknown, and even “invented histories” intersect and cohabitate (Zatzman 35-36).

The reality of and struggle with deferred dreams expressed throughout Raisin is an excellent example of Zatzman’s concept of shared experience. Beneatha Younger is a young African-American woman with an insatiable need to do and become something great. In her pursuit, she dabbles in many different forms of education and expression, but never sticks to one thing. She gains basic skills and understanding in a number of different areas, but masters none of them. She feels as though her family, who is supposed to love and support her and her dreams, is tearing them down. In a moment of frustration, Beneatha’s older brother Walter reprimands her for what he perceives as listlessness. “I don’t want nothing but for you to stop acting holy ‘round here,” he says. Why can’t you do something for the family? It ain’t that nobody expects you to get on your knees and say thank you.” Beneatha defiantly drops to her knees and retorts, “Well—I do—all right?—thank everybody! And forgive me for ever wanting to be anything at all!” (Hansberry 21)

Individuals who have felt denied or belittled by a family member can relate to this powerful scene. There is a touch of humor expressed by Beneatha, but she uses it to show the hurt that she feels. Every experience that the audience members can relate to this moment is connected with their personal history. As the audience watches Beneatha’s pathetic performance for her brother, their experiences fill in the information that is missing about their relationship. In other words, the information from the play and the experience of the audience intersect. This is the place where the remembered, forgotten, unknown, and “invented histories” can live (Zatzman 36).

The unique shared experience provided by theater evokes emotional responses between the actors and audience. “The aim of theater, like art, [is] to stir or provoke emotion rather than describe emotion,” says Kenneth Macgowan, a prominent theater critic of the early twentieth century (Bloom 96). Because the provocation of emotion is theater’s aim, emotion contributes to both the creation of each work and its appreciation. The dynamic between the creator and the observer is called “aesthetic emotion,” which means that there is a quality in the work that provokes emotions of the same kind (Bloom 80). Referring back to Beneatha’s experience with her brother, the emotion that is evoked in the audience is that of sadness, helplessness, or pain. As she screams an apology for “ever wanting to be anything at all,” the audience’s shared experience carries her emotion into their own hearts. The emotion with which the lines were written, and especially performed, is translated to the observer.

In the example afore noted, the actor’s performance plays a vital role in transferring emotion to the audience. According to Zatzman, when actors compile and reconstruct their own portrayal, “the obligation to witnessing and the performing of the identity is made vivid” (Zatzman 36). Vivid is a powerful descriptor in this context. Vivid can mean multiple things: producing a strong and distinct mental image, active or inventive, strikingly clear, or, most powerfully, truth to life when perceived either by the eye or the mind. One example from Raisin may help illustrate how vividly a character can be portrayed.

Lena Younger, the mother of Beneatha and Walter, receives an insurance check following her husband’s death. Walter went out to invest the check, worth $10,000, in a business venture and gets swindled out of all the money. A large portion of the check was going toward a down payment on a house in a nice neighborhood across town. Without that money the family has few options. A representative of the nice neighborhood visits the family to buy the house from them, because the white neighbors do not want any blacks around them. Walter, a broken man, considers taking the offer despite the complete lack of dignity it would show. He frantically performs his plan in front of his awe-struck family:

I’m going to look that son-of-a-bitch in the eyes and say—(He falters)—and say, ‘All right, Mr. Linder—(He falters even more)—that’s your neighborhood out there! . . . And you people just put the money in my hand and you won’t have to live next to this bunch of stinking niggers!’. . . And maybe—maybe I’ll just get down on my black knees [which he does to the sheer horror of the women in the room]. . . . ‘Captain, Mistuh, Bossman’—(groveling and grinning and wringing his hands in profoundly anguished imitation of the slow-witted movie stereotype) ‘A-hee-hee-hee! Oh, Yassuh boss! Yasssssuh! Great white. . . Father, just

gi’ ussen de money fo’ God’s sake, and we’s—we’s ain’t gwine come out deh and dirty up yo’ white folks neighborhood. . .’ (He breaks down completely) And I’ll feel fine! FINE! (He gets up and goes to the bedroom) (128).

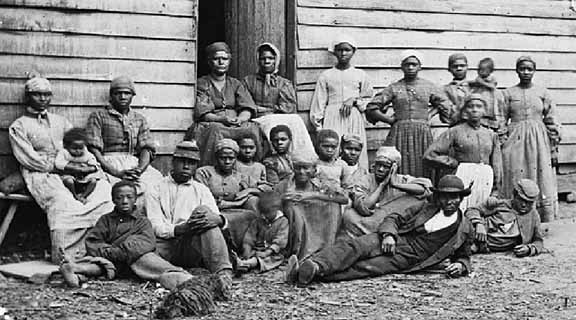

Walter’s performance is strikingly vivid. His actions provoke powerful mental images of slaves, broken individuals, who rely on the “benevolent hand of the white man” for their lives. His family’s reaction is “sheer horror.” Reactions from the audience are not likely to be much more positive. The vividness of his actions, in the eyes of his family, is expressed in a truth which once was; a truth that has been fought against, by their ancestors, for generations. As he breaks down, the emotion he exhibits is transferred to the observer.

Raisin’s shared experience and translated emotion combine to influence all parties involved to look inward. Professor Emeritus Walter A. Davis of Ohio State University says that “the purpose of serious theater can be stated simply—to challenge the audience to examine everything that they don’t want to face about themselves and their world” (Davis 3). There is no other public institution, according to Davis, that can publicly air secrets like theater can. Every other institution is established to celebrate and perpetuate ideology. “Freedom,” says Davis, “depends on overcoming the vast weight of ideological beliefs that have colonized one’s heart and mind” (Davis 3-4). The purpose is not to convince the audience to change their ideas. “Serious drama strikes much deeper. It is an attempt to assault and astonish the heart, to get at the deepest disorders and springs of our psychological being, in order to effect a change in the very way we feel about ourselves—and consequently about everything else” (Davis 4).

Robert Nemiroff, the late Lorraine Hansberry’s husband, wrote an introduction to the script of Raisin. He quotes James Baldwin, who says that Americans suffer from an “ignorance that is not only colossal, but sacred.” He refers to our seemingly infinite capacity to lie to ourselves about race issues (qtd. in Hansberry xviii). These farcical ideas become entrenched in the mind and heart. It takes a major event to shake these ideas loose. The powerful emotional experience available from Raisin is closely tied to the race issues that are portrayed therein. It is difficult to feel Walter’s pain with him and not see the degrading nature of his portrayed relationship with the housing representative. Experiencing this with him can indeed be a traumatic event. It is through a traumatic event such as this, argues Davis, that we learn something about our character that reveals the lies within us. More importantly, he claims, we learn that we are the “author of the events that brought us to this situation” (Davis 122-23). It is then up to each individual to choose to do with that new knowledge.

Together, shared experience, emotional inducement, and the influence to look inward make Hansberry’s choice of medium powerful in facilitating the expression of her main themes. Now, over a half-century later, A Raisin in the Sun is still as widely acclaimed as ever. Not only do the themes penetrate through generations, but the theater instills their perpetuation in all who participate.

(There is an interesting post by one of my graduate instructors, Brett Sigurdson, that includes some interesting videos of A Raisin in the Sun, both during the 60s and today. It's worth taking a look at. http://english3300.wordpress.com/2011/02/19/a-raisin-in-the-sun-then-and-now/)

Works Cited

Bloom, Thomas Alan. Kenneth Macgowan and the Aesthetic Paradigm for the New Stagecraft in America. New York: Peter Lang, 1996. Print.

Davis, Walter A. Art and Politics: Psychoanalysis, Ideology, Theatre. London: Pluto, 2007. Print.

Hansberry, Lorraine. A Raisin in the Sun: 1995 Modern Library Edition. New York: Random House, 1995. Print.

Pitman, Walter. “Drama through the Eyes of Faith.” How Theatre Educates: Convergences & Counterpoints. Ed. Kathleen Gallagher and David Booth. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2003. 162-172. Print.

Zatzman, Belarie. “The Monologue Project: Drama as a Form of Witnessing.” How Theatre Educates: Convergences & Counterpoints. Ed. Kathleen Gallagher and David Booth. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2003. 35-55. Print.