Political and social discourse in the mid-eighteenth century was charged with the issue of slavery. The nation was divided between pro-slavery sentiment and anti-slavery sentiment, with some staking out the middle ground. Harriet Beecher Stowe stakes her claim among the anti-slavery sentiment in her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. With literary proficiency, Stowe claims the diabolical inception of slavery as an institution, describes the horrors of the slave trade, and pleads for freedom to all individuals. Many Southern authors write in direct response to the negative claims made in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. One significant example is Aunt Phillis’s Cabin, by Mary Eastman. Eastman claims the divine origin of slavery, portrays the improved and happy state of black slaves, and points out the unethical, indeed hypocritical, nature of abolitionists. Stowe and Eastman exhibit many opposing, and some similar views. This analysis will consider some of the main differences between the two opinions, followed by a consideration of some of their similarities. A few significant topics will then be reviewed from each author’s point of view: slaveholders, opponents to slavery, the societies of the North and the South, and the idea of freedom.

There are a few key differences in the way Eastman and Stowe analyze the institution of slavery. Mary Eastman’s argument is based partially on a certain interpretation of the Bible. Ham, the son of Noah, brought the wrath of God upon himself because of sin. God cursed Ham and his posterity to forever be a subservient race to God’s chosen people (E, 13-15). According to Eastman’s interpretation, this curse has existed since that time. Southerners enslave Africans, because they are direct descendents of Ham. Eastman says there is no reference in the Bible condemning those who enslave the “heathens” (E, 15-16). On the contrary, God’s Biblical Prophets held slaves. When Jesus came he did not free the slaves, though he encountered many, nor did his Apostles after he died (E, 18-20).

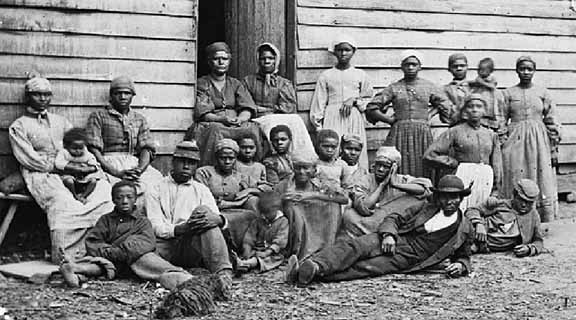

Along with her argument that slavery is sanctioned by the Bible, Eastman claims that Southern slaves are much better off as slaves than they would be otherwise. Once they finish their daily chores, the slaves can enjoy their evening pleasantly. In Eastman’s words, they are “all at ease, and without care.” Their cabins are neat and clean, where they can relax in their scene of real enjoyment (E, 30). When they are freed, slaves are never as happy or comfortable as they were with their master. Susan is Eastman’s runaway example. “Poor Susan!” Eastman laments. She has absolutely no means, no money. Her guilt for leaving her mistress is piling on her and her feelings are constantly agitated. Truly, according to Eastman, Susan feels she is “out of the frying pan and into the fire” (E, 58-61). At least with her mistress, Susan was well provided for and she was at peace.

Stowe argues that slavery has a much more sinister birth than that claimed by Eastman. According to Stowe, slavery comes from the devil himself. The devil provides slavery as a tool for men to use in worldly pursuits. Planters use it to make money—the love of which, according to the Bible, is the root of all evil. Clergymen use it to please the planters, who in turn do favors for the clergymen. Politicians use it to rule by, and are sustained by the planters and clergymen (S, 331).

Because the devil himself is at the root of the peculiar institution, Stowe claims that “it is impossible to make anything beautiful or desirable in the best regulated administration of slavery.” Kentucky is seen as one of the most virtuous regions for slavery, yet slaves in that region must always fears the possibility that they will end up down South with a vicious planter (S, 51).

Because the devil himself is at the root of the peculiar institution, Stowe claims that “it is impossible to make anything beautiful or desirable in the best regulated administration of slavery.” Kentucky is seen as one of the most virtuous regions for slavery, yet slaves in that region must always fears the possibility that they will end up down South with a vicious planter (S, 51).

Eastman and Stowe do have a few areas in which their analyses of slavery overlap. One major similarity between the two is their view of the slave trade, primarily the splitting up of families. In Aunt Phillis, the main planter, Mr. Weston, tells a story about Lucy, a slave woman whose children have all been sold away. She is immensely distraught and heartbroken, and her story has a powerful impact on Mr. Weston. He says that he looks upon this act, namely the splitting up of families, with “horror.” In his opinion, “it is the worst feature in slavery.” According to Weston, this act is quite uncommon, because most men have more virtue than that, and those who don’t would lose their reputation in the neighborhood (E, 44-45). Stowe likewise cites the sale of a child away from its mother. After Tom, an exceptionally pious slave, loses his kind master he is put up for sale to the highest bidder. The night before the auction, all the slaves are locked in a large warehouse. All through the night and into the morning, slave owners and traders come in to check the selection. They do so as they would a piece of livestock: checking the hands and feet, inspecting the teeth, having them perform small tasks to prove their soundness. Tom is sold to a gruff man, who also buys a young woman and her new child. They board a ship to head for their new home, and as the woman sleeps the man sells the child to a man as he disembarks. The woman is absolutely distraught (S, 467-479). Stowe uses this example to show the barbarity and selfishness that is involved in such an act.

Another similarity between Stowe and Eastman’s analyses is the effect of slavery on slaveholders. Often, according to Eastman, slavery is just as hard on the master as it is on the slaves. Mr. Weston looks at the “grieving, throbbing souls” and wonders that God has not provided a solution. It is true, he acknowledges, they did sin, but what a terrible punishment. If there was an easy way, and a just way, for emancipation and colonization he would do it; unfortunately there is no easy way (E, 234-235). Stowe uses St. Clare as an example of how slavery impales slaveholders. After his cousin, Miss Ophelia, accuses him of defending the institution, he says to her that if the whole country would sink as a result of this horrible sin of slavery, “I would willingly sink with it” (S, 332). He was born into the chattel system as the son of a planter. When his father died, he inherited half of his slaves, and seeing no rational or worthy way to rid himself of the horrible system, he has stayed. It hurts him every day to think that these people he holds as servants are not, and most likely never will be, free (S, 329-344).

As can be seen in the previous analyses, Eastman and Stowe portray slaveholders in some interesting ways. Eastman argues that discipline and redirection are handled much more humanely than many Northerners think. It is common for a slaveholder to talk issues through with their servants, rather than always resorting to violent measures. Mr. Weston explains issues to his servants and lets them know exactly what he expects of them. When his servant Phillis admits to him that she let a local runaway sleep in her cabin, he tells her that he understands why she did it, but makes it clear that she is not to do it again. He explains that the runaway is nothing but a trouble maker, and that the laws of the land must be respected. With that, he sends her back to her work (E, 116-119). This interaction portrays slaveholders as fathers to their servants, trying to show them the way. Thus it is in the slaveholder’s best interest to make keep his slaves happy (E, 45).

Stowe’s view of slaveholders is less idealistic than Eastman’s. Stowe admits that there are likely many slaveholders who are good men. They are a part of the slave system simply because they were born into it. The example of St. Clare has previously been mentioned. He is good at heart, and wishes there was more he could do to effectively improve the slaves’ position (S, 329). According to Stowe these are not, however, the majority. A system which was founded by the devil, as Stowe claimed, has a greater tendency to corrupt men, and lead them to as much temptation as possible. These men are more likely to run things by force and fear. Any slave who chooses to defy the master’s decision or direction is beaten into submission. The master enjoys it, and is proud of his accomplishment (S, 483-484). It is a slippery slope, according to Stowe’s narration. If slaveholders feed the passion for and enjoyment of beating slaves into submission, that passion can lead a man to kill out of sheer passion (S, 539-540, 557-558, 578, 582-585). Thus, slavery has an astonishing ability to corrupt men. Corruption can, however, also come from the opposition: the abolitionists.

Abolitionists are treated differently between Eastman and Stowe. Eastman portrays abolitionists as hypocritical, telling southern slaveholders to give up what is rightfully theirs, but “does he offer to share in the loss? No.” According to Eastman, these “fanatics” will never bring about the emancipation of the slaves. Indeed, it will never happen by force, but by God’s will only (E, 51). Abolitionists “seduce” slaves to run away, but that is as far as their Christian virtue goes. They are otherwise concerned about their own time and money (E, 58, 60). Eastman says that the abolitionist cause would be much more respectable with “a few flashes of truth” (E, 119). This view of the opponents of slavery comes off quite harsh, and that is Eastman’s point. Abolitionists are seen by Southerners at the time as sinister little devils, trying to concoct a way to ruin the entire Southern way of life.

Stowe’s portrayal of abolitionists is much less harsh overall. Early in the book, Stowe introduces a kind hearted woman in Kentucky that believes that slavery is wrong. All she wants to do is help the “poor creatures” by giving them a place to sleep, some food to eat, and some clothes to wear. She does not intend to hide them there at her home, but simply to be a good Christian, indeed a Good Samaritan (S, 142). Her husband, a Senator, had voted to pass and uphold the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. However, upon personal experience with a ragged runaway slave, the Senator’s heart is touched and he himself helps the runaway (S, 147-161). In an attempt to avoid oversimplification, Stowe points out that many abolitionists are just as racists as any slaveholder. They want freedom for the slaves, but beyond that they want nothing to do with them. Miss Ophelia is astonished that St. Clare lets his children kiss the servants. She is thoroughly disgusted with the sight (S, 255-256). This portrayal is similar to Eastman’s, but employs a slightly softer tone, suggesting Stowe’s concern for offending good-hearted abolitionists.

Eastman and Stowe agree that Northern society is not as virtuous as its citizens claim it is. Eastman revealed the secret of Northern emancipation: they were “relieved from the necessity of slavery” (E, 23). If the Northern economy was still based on large-scale agriculture, they would likely still have slaves to do the work. Because of the shift toward manufacturing and commercialism in the North, there is very little need for a workforce of slaves. Yet the Northerners feel they have a right to judge the actions of the South, which judgments, Eastman claims, are based on false information (E, 71). These hypocritical Northerners turn around and treat those of Irish descent worse than Southerners treat their black slaves (E, 73-74). Stowe gives an example of Northern hypocrisy. Miss Ophelia, St. Clare’s cousin, is from New England. She has come down South to stay with her cousin, because his wife is sick and cannot run the estate. Miss Ophelia constantly talks about what she would do if she were a slaveholder. She would be kind, and try to teach them right. As a playful test, St. Clare buys Miss Ophelia a slave girl named Topsy, and tells her it is her opportunity to teach her. Miss Ophelia is horrified, and says that she does not want anything to do with “that thing,” which is so “heathenish” (S, 351-353). If emancipation were to take place, Northerners would need to change the intense racism they exhibit, and that is as hard a task as emancipation.

Southern society is exemplified by both Eastman and Stowe largely through women. Eastman describes Southern society as virtuous and decent. Southern women, according to Eastman, have a lot of class and are very understanding of others. They are very kind to their servants. At the periods of the day designated for rest, white slave owners do not call on their slaves for help, because they respect the fact that the slaves have very little that brings them pure joy (E, 163). Indeed, Eastman argues, the South is much more virtuous and humane than many Northerners think. If they would but come to the South, they would see it (E, 206).

Stowe’s view of the South is very different from Eastman’s. When people are surrounded by servants their entire life, they become selfish, cynical and harsh. Marie St. Clare, the slaveholder’s wife, is the woman onto whom Stowe packs all of these unfortunate traits. Because she grew up wooing all the men within her society, Marie thought St. Clare was very lucky to have her. She takes and takes and does not give anything back, especially when it comes to love (S, 242). Marie is very cynical about other people and their motives, especially slaves, due to her extensive experience with the chattel system (S, 257). Marie, and through interpretation Southerners as a majority, have become rather harsh. Marie believes that the only way to keep a good slave is to break them: put them down and keep them down (S, 265). This portrayal shows some major defects within Southern society, and suggests a possible flaw in Southern ideology.

The idea of freedom, and the way in which that idea is portrayed, is very different in each of the two works. Eastman portrays freedom as an ambiguous thing. Abolitionists, Eastman argues, want to give slaves their freedom, namely the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. When they remove these slaves from the plantation, they provide them with no means to accomplish those pursuits. How could emancipating the slaves provide them with these liberties if they have absolutely no means of accomplishing the ends described (E, 66-68)? On a religious note, Eastman returns to her point that slavery was instituted by God. Because it was a commandment of God, only he can emancipate the slaves. Freedom is something that no man should take, even for himself. Eastman uses her character Phillis as an example. Phillis’s master takes her North with him on business, where she is encountered by abolitionists. They ask her why she does not just leave, and take her own freedom. She replied that if her master were to give it to her, she would be more than happy, but she would never take anything, including her freedom (E, 103-104).

Stowe’s view of freedom is very different from Eastman’s. To Stowe, freedom is not ambiguous. Freedom is what every man yearns for. After St. Clare tells Tom he will set him free and let him return to his family Tom is ecstatic. St. Clare asks him if he has not been well provided for, because in fact Tom clothing and home would not be nearly as nice as they are now if he were a free man. Tom said that he had been very well provided for, but he would rather have poor man’s clothing, home and everything, “and have ‘em mine” than have nice things (S, 441). For Tom, freedom is the most desirable thing in the world. Stowe asks, “What is freedom to a nation, but freedom to the individuals in it?” Freedom to Stowe is not identified by a nation. If a nation claims to be free, it means nothing unless the individuals therein are free: individuals with “the right to be a man, and not a brute;” men free to protect their wives and educate their children (S, 544-545). Freedom is for individuals.

Overall, Stowe portrays the institution of slavery as fundamentally flawed and immoral. As a result of its wicked inception, individuals and societies that allow and revere the institution are negatively affected. There is no easy solution to the problem; nevertheless, the problem needs to be dealt with. Eastman suggests that the peculiar institution is established by God, and though there are some vices connected with this way of life, the virtues and humanitarianism found therein greatly outweigh them. Both works conclude with an appeal to a higher power, calling on the North and the South to remember that they will be held responsible before God for their actions (S, 629, E, 281). Ultimately, Stowe seeks action to eventually end the slave system; Eastman seeks action, from the North and the South, to take care of their own poor. These opposing views translate into a larger, socio-political sphere where discourse of this nature continues throughout the eminent war between the two regions.