American nature writers left a

vision of fantastic beards and superfluous descriptions in my mind. Transcendentalists

during the early nineteenth century practiced nature writing through individual

experience and observation of nature, seeking a spiritual connection therein. Postmodern

America of the late twentieth century bred a new generation of nature writers,

studying the connection between the way we think about nature and the health

and preservation of the natural world. A close analysis of traditional nature

writers from the perspective of these new ecocritics, as they have been termed,

reveals the interdependence of humans and nature.

The literal and

metaphorical vision employed by American nature writers—through which humanity

gains experience and understanding of its interdependence with nature—has

changed. Early in the tradition, the vision of Transcendentalist nature writers

was focused on each person’s individual experience with the sublimity of

nature. Individual experience was central to the writings of Ralph Waldo

Emerson and John Muir. Over the span of one-hundred and fifty years, nature writing

has moved from a focus on individual experience to a focus on collective

experience and influence. Ecocritics have set the foundation for the social and

political focus that is, and must be the future of American nature writing,

exemplified so well by Terry Tempest Williams.

|

| Ralph Waldo Emerson |

Ralph

Waldo Emerson was one of the key figures in the Transcendentalist literary

movement in the early nineteenth century. Observation and vision were central

to his literary and environmental theory. Truly seeing nature as an individual

was the best way to experience the divine. Few people, according to Emerson,

can actually see nature. Theirs is but a “superficial seeing,” merely

scratching the surface of what can and should be observed (7). According to

Emerson, “the eye is the best of artists” (13). The art of which he spoke was

explained by one critic through Emerson’s pattern of observation. Both he and

his good friend Henry David Thoreau bounced between “local observations” and

“visionary exaltation,” creating a distinct rhythm (Elder vii). Emerson’s

vision stretched beyond what he simply gathered with his eye. “Man is an

analogist,” Emerson said, who constantly views the world and makes connections

in order to understand their relation (24).

Viewing

Emerson’s vision through the lens of contemporary ecocritics reveals nature’s

human inception in his writings. William Cronon, a Rhodes Scholar and

environmental historian, said that wilderness is a “human creation,” and a

“product of civilization” (69). Wilderness was historically negative, depicting

a deserted, savage, and dangerous land. Biblical references made wilderness out

to be harsh, and a place of trial and famine. Slowly the common vision of

wilderness changed. What was once “Satan’s home” was now “God’s own temple” (Cronon

70-71, Nash xii). Wilderness became not only a place for religious renewal, but

for national renewal. As the frontier “closed,” Americans needed a place to

turn for relief from the woes of civilization, and that place became the

“wilderness” (Cronon 76).

A well-to-do Ralph

Waldo Emerson turned his eye toward the wilderness, and the wilderness was

defined by how he saw it (Cronon 79). By rightly seeing the objects of nature,

however, new faculties of the soul are also unlocked (Emerson 31). Emerson emphasized

sight, insisting that each individual “witness” the spectacle around them for

themselves, for by so doing they would define both nature and themselves (Elder

x-xi). Emerson was convinced that when man opens his eyes properly to view the

world around him, he is able to see into the heart of nature, and therefore the

heart and mind of God. As he takes a small moment in time, Emerson, works it up

with grandiose rhetoric in a production of Transcendental vision (Elder

viii-ix). Emerson’s observations and elaborations are an attempt to see and

point out the true position of nature in relation to man, because this view is

the most desirable to the mind (Emerson 43, 51-52).

Much of Emerson’s

maxim on vision was based on where to focus. By focusing on the science behind

nature, “the end is lost sight of in attention to the means” (Emerson 61). To

use another analogy, by paying too much attention to the pieces of a puzzle,

the entire picture cannot be understood and the purpose of piecing the puzzle

together is lost. Emerson understood that wildness was not just large amounts

of unsettled land, but “a quality of awareness” (Elder xvi). What an individual

sees in nature is a direct result of his vision. If man sees ruins or blankness

in nature, it is because of his own eye. His “axis of vision,” according to

Emerson, needs to be in line with the “axis of things,” otherwise they become

“opaque” and impossible to understand. Individuals must then look at the world

in the mode of Emerson. If they do, they will do so “with new eyes,” because

“what we are, that only can we see” (64, 66).

|

| John Muir |

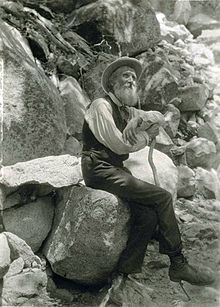

If Emerson was the

perfect example of the visionary man, John Muir was the perfect example of the

rugged individual, wilderness loving American man. After having immigrated to

the United States from Scotland as a young man, Muir grew up on a farm in

central Wisconsin where his father placed him within strict boundaries. His

creativity could not be contained, however, and Muir left home to attend

college at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. While at school, Muir

studied hard in chemistry and built bizarre contraptions in his apartment.

After a few years of course work, Muir left the University of Wisconsin for

“the University of the Wilderness” (Muir 21).

Following his time

at the University, Muir hiked to many places throughout the continental United

States and Alaska with nothing but a small pack including a change of clothing

and a couple of books. Muir foolishly risked his life as a “Transcendental

mystic who over-rhapsodized the sublime beauty of the wilderness” (White ix).

Muir’s insatiable need for knowledge and experience almost put him in the

ground on multiple occasions. He had a number of near-death experiences,

including one on a road in Florida where he was luckily found by a man who took

him in and revitalized him, and a near slip on a sheer rock wall hundreds of

feet up from the ground in the Sierra Nevada Mountains (Muir 30-34, 46-49).

Despite these hair-raising experiences, or perhaps because of them, Muir was

able to utilize his education and fuse his poetic, geologic, and botanic

visions together. He viewed nature as “infused with spirit.” He was neither

scientific nor literary, but “a fusion of both,” creating a very unique product

resultant of his return to primitivism (White ix, xi, xiv).

Muir not only

exemplified the wild man, but did so with profound vision. Everywhere he went

he recognized and noted every piece of flora and fauna he came across. Muir’s

was not a “superficial seeing,” but a truly Emersonian ability to see into and

through nature in a way that embodied one of his favorite words: sublime. After

his brush with death in the Sierra Nevadas, Muir stood atop the peak and gazed

across the landscape in every direction. His senses had been intensified during

his experience, and now he could see what was really there, and it was truly

“glorious” (48). In a letter he wrote to his long-time friend Mrs. Jeanne Carr,

Muir said, “All depends upon the goodness of one’s eyes,” and Muir’s own were

able to see the glorious and sublime all too well. In perfect synthesis of his

wildness and vision, Muir understood that he could not remain uprooted from the

earth for long without “losing [his] sense of what it means to be fully alive”

(White xiv, xx).

Over time, the sublime-individualistic

vision of Emerson and Muir evolved into a study of humanity’s influence on the

natural world. Lawrence Buell, a renowned Professor of American Literature, is

a pioneer in the field of environmental criticism. Also referred to as “ecocriticism,”

this emerging field is the study of the relationship between literature and the

physical environment (Buell 11). During the last three decades of the twentieth

century, the environment moved into the forefront of American discourse and was

the subject of many books and articles (Buell 4). The surge of conversation and

rhetoric about nature was largely a result of a growing awareness that humans

had a profound influence on the state of nature around them. Until this point

in time “setting” had been seen as simply a backdrop, a building block for good

literature. Ecocritics saw setting and nature as so much more than that. Similar

to Transcendentalist nature writers, early ecocritics focused largely on

experiencing and understanding personal orientation with nature. Reading and

living personal experiences with the environment was central to their goal. Over

time, a second wave of ecocritics emerged, focusing on social and political

implications of the environment (Buell 8)

One

thing that set the second wave, or second generation, of ecocritics apart from

the first was their focus on vision. “Vision, value, culture, and imagination,”

according to Buell, were just as important to second-generation ecocritics as

science, technology, or legislation (Buell 5). There were some major issues

regarding the destruction of the American environment that these new nature

writers were trying to change, or at least make known. Nature writers branched

out and ecocriticism became interdisciplinary, greatly broadening the study,

view, and influence of their rhetoric (Buell 7). This “wide-open movement”

gathered momentum and grew very rapidly (Buell 28). The aim of these environmental

writers, Buell said, was to change American status quo thinking about the environment

(24). This allegedly flawed thinking was a result of long established cultural

sentiments about what defined wilderness.

|

| Roderick Nash |

In

his book Wilderness and the American

Mind, Roderick Nash claimed that wilderness “was the basic ingredient of

American civilization” (xi). The word “wilderness” was likely derived from the root

word “will,” as in willful, but eventually became defined as large tracts of

uncultivated and undeveloped land. Despite the apparent etymology of the word,

“wild” has proved an elusive term to define. It has been consistently

subjective within American culture, with many interpretations and meanings

depending on situation and context. Nash cited one common definition of wild: that

which is outside the control of mankind (xiii-5).

Nash

moved from defining the terms wild and wilderness to outlining their social and

cultural implications. Over time “wilderness” transitioned from a negative word

associated with desolation and pestilence to a positive word associated with

freedom and happiness. This was especially true in America, where there had

been a physical frontier to which people could turn for social or financial

redress. As that line slowly moved west and disappeared, Americans looked to

wilderness as their new frontier, where man’s degeneration to the primitive

would free him from social constraints (Nash 48). Nash cited Benjamin Rush, a

signatory of the Declaration of Independence, in claiming that man is a wild

animal, and will never be happy or at home until he is back in the wilderness (56).

This sentiment became commonplace across America, especially with the help of

Emerson and other Transcendentalists.

|

| Terry Tempest Williams |

As

we move from a study of the classic nature writers and Transcendentalists to

modern nature writers, it is important to note that vision has become more

important than ever. In her article “One Patriot,” Terry Tempest Williams uses

the example of one individual to invoke vision leading to social and political

action by the masses. Quoting Proverbs 29:18, Williams states that “where there

is no vision, the people perish.” According to Williams, America does have

people with vision, and therefore has the ability to both understand the issues

surrounding nature and act on them. Unfortunately, Williams says, the “pages of

abuse on the American landscape still lie unread” (39-40).

Williams

uses the example of one woman named Rachel Carson to help open the eyes of the

American public. Rachel Carson had vision. In her book Silent Spring, Carson chronicles nature’s destruction and death

caused by certain pesticides. Despite heavy opposition from chemical companies

and their representatives Carson stayed the course. Though at the time they

called her a fanatic and a fool, her observations were true. Many of the

pesticides were not only killing local fauna, but were getting into the local

food and drinking water. Carson’s objective was to open the eyes of the

American public to the horrible effects of these chemicals so they will take a

stand against them (Williams 39-41).

Williams’

agenda was similar to Carson’s. It is unfortunate, but Americans’ visions are

blurred by corporations and their myths about what is good and what is not good

for nature. They cannot see that their lives are knit closely together with

other life forms on the earth, fauna and flora. It is a fact, according to

Williams, and opening the eyes of the American people has become a major

objective of contemporary nature writers and ecocritics. It is likely that as

was the case for Carson, the vision needed to pursue environmental change and

protection will blur or fade, and both ecocritics and the American population will

lose sight of it. When it flashes again, it is important for them to try to

hold on to it and “keep the vision before [their] eyes” (Williams 41-42). As

Carson said, if there are dangerous and potentially damaging things happening

to the environment, “we should look around

and see what other course is open to

us” (quoted in Williams 51, italics added). Though Carson suffered through

cancer for much of her life, she “never lost ‘the vision splendid’ before her

eyes,” and Williams argues that we cannot lose it either (Williams 53).

If

nature writing is going to continue in the future, it must perpetuate the Williams

vision. Ideas and goals will change according to the issues of the times, but

nature writers will need to focus on political and social activism. Since its

inception the general American trend has paralleled that of nature writing. The

movement from individualism to, for lack of a better word, collectivism

outlines this need. Broadening the discipline will inspire more writers and

broaden its influence.

Vision’s progression through the

tradition of nature writing began largely with the man who could, along with

Walt Whitman, be considered the father of the genre. Emerson described vision as

essential to the understanding of nature and its implications on the individual

human soul. The Emersonian vision was central to the wildness of Muir’s own

understanding of the glorious and sublime. Modern ecocritics such as Buell,

Cronon, and Nash have brought vision to the forefront of contemporary

environmental writing, as evidenced in Williams’ piece. A study of this wide

variety of styles and pieces reveals that in general, American nature writers

argue that man’s interdependence to nature is understood and experienced

through vision, both literal and figurative. It is only as man truly opens his

eyes that he can see the world around him. It is only as man begins to truly

see the world around him that he can see and understand himself.

Works

Cited

Buell,

Lawrence. “The Emergence of Environmental Criticism.” The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary

Imagination. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005. 1-28.

Cronon,

William. “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.” Uncommon Ground: Toward Reinventing Nature. New

York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 1995. 69-90.

Elder,

John. “Introduction: Sauntering Toward the Holy Land.” Nature and Walking. Boston, MA: Beacon, 1992. vii-xviii.

Emerson,

Ralph Waldo. Nature. in Nature and Walking. Boston, MA: Beacon,

1992. 3-67.

Nash,

Roderick. Wilderness and the American

Mind. New Haven, CT: Yale U.P., 1982.

Muir,

John. Essential Muir: A Selection of John

Muir’s Best Writings. ed. Fred D. White. Santa Clara, CA: Santa Clara U.P.,

2006.

White,

Fred D. “Introduction.” Essential Muir: A

Selection of John Muir’s Best Writings. ed. Fred D. White. Santa Clara, CA:

Santa Clara U.P., 2006. ix-xx.

Williams,

Terry Tempest. “One Patriot.” Patriotism

and the American Land. Great Barrington, MA: The Orion Society, 2002.

37-57.

No comments:

Post a Comment