|

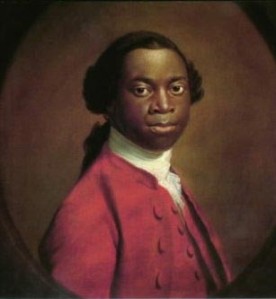

In his autobiography The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah

Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, identity was one of the author’s

central themes. Intentionally or unintentionally, the author portrayed his

identity as dualistic and dichotomous. This dichotomy was especially pronounced

in the use of his two names and in the descriptions of Africa and England, his

two homelands. Both of these examples exuded subtle clues that suggest the

author’s identity as an English Christian. Vassa clarified his identity through

the comparative descriptions of his native African religion and his

then-current Christian religion.

The

first dichotomy Equiano portrayed in his narrative was the use of his names. The

title of his book included both names by which he was known during his life.

The first name listed was Olaudah Equiano, his African name. The second name he

listed was Gustavus Vassa, the name he was given by his owner en route to

England for the first time. This order implied the name by which he preferred

his narrative to be known. Equiano chose to add the phrase “the African” to the

title in an attempt to maintain a connection to his land of origin. The name Olaudah

represented the folk spirit of Africa, and as an African, Equiano’s story portrayed

a stronger ethos to readers.[1]

Though

the author chose to state his African name Olaudah before his given name

Gustavus, he almost exclusively used the name Gustavus throughout his life.

When aboard a ship to England, the author told his master that he wanted to be

known as Jacob. His master refused and gave him the name Gustavus Vassa.[2]

The author used the name Gustavus as he moved from owner to owner, and later after

he bought his freedom and traveled as a free sailor. Likewise, when he was

baptized and later became a missionary to Africa, he continued to use the name

Gustavus.[3]

The author would have had more clout connected to the name Gustavus than

Olaudah among the white community. He may not have been able to make some of

his necessary relationships or business transactions with an African folk-name

like Olaudah. This tension represented the author’s inner struggle to define himself,

both as an African and an Englishman without completely giving up either.

The

second dichotomy Equiano portrayed in his narrative was his sense of home. In

the first chapter of his book, Equiano described in detail the society in which

he grew up. Equiano portrayed his African society—many miles inland from the

Bight of Benin—as very considerate and moral. They established families, made

official through a ritualistic marriage ceremony. They exchanged manufactured

goods and participated in commerce; they fought wars, and took slaves of their

own.[4]

Later in his life Equiano returned to Africa, the land of his birth, as a

missionary to try and convert his brethren to Christianity. This excursion

highlighted the duality of his view of home.[5]

England

became Vassa’s new homeland. He sailed to England fairly soon after his trip

across the dreadful middle passage. In England he felt the strongest connections

to other people since his sister was taken away from him in Africa. He was able

to make friends and learn about Christianity. He was baptized and eventually

learned to read, allowing him to delve deeper into the religion.[6]

When Vassa was forced to sail to the Mediterranean he deeply wanted to return

to his new home in England. Later, when his master betrayed him and sold him to

the West Indies, his greatest desire was to return to his beloved England.[7]

After Vassa obtained his freedom he returned to England again and again,

working as a free sailor and earning his wages.[8]

This series of events suggests that Vassa had an emotional connection to

England. Despite his very positive descriptions of Africa and his trip as a

missionary, Vassa’s heart always remained in England. It was this trip as a

missionary that highlighted the last dualistic portrayal of the author’s

identity.

The

third dualism Equiano portrayed was his religious identity. This side of his

identity was different than the previous two in that his religious identity more

notably changed over time. This aspect of his identity was also much easier to

define. In the first chapter of his book, Equiano described the religious

beliefs and practices from his homeland in Africa. His society had a

ritualistic marriage tradition, after which the woman became the sole property

of the man.[9] They

believed in one Creator of all things, who lived in the Sun and controlled all

the events of their lives. Equiano recalled no concept of eternity, but rather

a form of transmigration of souls. Some souls were transmigrated to other

people or objects, and the souls that did not would attend their families

forever. These souls were central to religious rituals practiced there.[10]

Vassa

seemed to have completely renounced the religious aspect of his African

identity after he learned of Christianity. In February 1759 Vassa was baptized

and began his life as a Christian. He knew enough about the religion that he

thought he would go to hell if he was not baptized, a fact that his mistress

stressed repeatedly.[11]

From this time forward Vassa constantly looked toward this religion in times of

peril or heartbreak. When his master sold him to the West Indies he argued that

his master had no right to do so, for he was a Christian.[12]

Vassa spent an entire chapter describing his full conversion to the faith. He

was distressed and began to pray to God for redemption. As a result he claimed

to have marvelous visions while he slept which left him “resolved to win

heaven, if possible.” He “kept eight out of ten commandments,” but that just

was not enough.[13]

He continued to work, and began bringing others into the fold. It was then that

Vassa went on a mission to Africa. This event was an expression of one of the

most telling points of his religious identity. He chose to leave his land of

England, to which he had become most accustomed, in an attempt to convert the

poor Africans who knew not of Christ. This suggested a complete renunciation of

his old beliefs, and showed that he felt it would be best for all Africans to

do the same. Gustavus Vassa was a Christian.

Despite

the author’s dichotomous descriptions of his own identity, subtle evidence indicated

his identity as an English Christian. His identity changed over time, away from

his folk-customs, society, and religion of Africa and toward his Christian,

sailor, gentlemanly customs of England. He placed his African name first, yet

used his given slave-name most of his life. He described the civilized culture

of his Africa, yet embraced the civilized culture of England. Most of all, He

renounced his spiritualistic religion of Africa for Protestant Christianity.

The author exemplified his dualistic identity in his closing remarks to the

Queen, “I am, your Majesty’s most dutiful and devoted Servant to command,

GUSTAVUS VASSA, The Oppressed Ethiopian.”[14]

[1] Olaudah Equiano, The Interesting Narrative of the life of

Olaudah Equiano, or Gustavus Vassa, the African, 1814, in The Classic Slave Narratives, ed. Henry

Louis Gates, Jr., (Penguin: NY, 2002) 15.

[2] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 66.

[3] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 81, 229, 230.

[4] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 29-39.

[5] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 228.

[6] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 67, 81.

[7] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 88, 98.

[8] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 166-183.

[9] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 32.

[10] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 39-40.

[11] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 81.

[12] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 97-98.

[13] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 191-192.

[14] Equiano, Interesting Narrative, 247.